So far we have learned how to define String objects, assign them values, and concatenate (+) them, but there is much more we can do with strings! We’ll start with three important facts to know about strings, and then cover many of the rich set of String methods in Java.

Fact #1: Strings are Objects

In 1-2 we learned that strings are objects and not a primitive data type because they include methods, such as equals(). You’ll recall that when we have created other objects (like Scanner) we’ve needed to use the new keyword to instantiate (create) the object:

|

1 |

Scanner input = new Scanner( System.in ); |

Yet when we’ve created String objects the new keyword has not been necessary:

|

1 |

String shortWay = "Short-hand way to declare a string."; |

Why is this? The reason is that since strings are so commonly used in Java the line above is accepted shorthand for instantiating a String object. The Java compiler actually interprets the line above as if you had typed something like:

|

1 |

String longWay = new String( "Proof that strings are really objects!" ); |

Proof that strings really are objects! Both ways of declaring a String work but I think you’ll agree that the shorthand way is more convenient. This shorthand only works for String objects.

Fact #2: Strings are Immutable

The next important thing to understand about String objects is that they are immutable. Immutable means that once a string object has been assigned a string value, that value may not be changed. Consider the following example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

public class Immutable { public static void main( String[] args ) { // declare one String object and one primitive (int) variable String message = "Hello"; int age = 16; System.out.println( message + ", I hear you are " + age + " years old!" ); // Let's "change" these variables message = message + " James"; age = age + 1; System.out.println( message + ", I hear you are " + age + " years old!" ); } } |

As you would expect, the output of this program would be:

Hello, I hear you are 16 years old!

Hello James, I hear you are 17 years old!

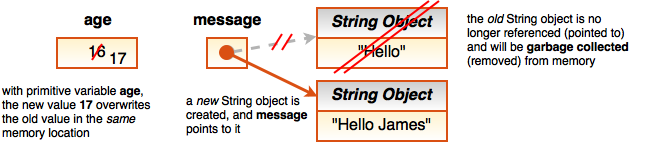

On the surface it appears that String and int variables are modified in the same way, but it’s critical to understand what is actually happening behind the scenes. After line 6 executes, the age and message variables look like this in memory:

After line 10 executes, this is what happens to them:

After line 10 executes, this is what happens to them:

You can see that when the primitive int variable age is modified on line 10, the memory location that contained its initial value (16) is simply overwritten (recycled) with the new value (17). For the String object message it works differently. Rather than overwriting the String “Hello” in memory, a brand new String object “Hello James” is created and the message reference variable then points to this new String in memory. Because the old String object “Hello” no longer has any references (arrows) pointing to it, the JVM will remove it from memory by an automatic process called garbage collection. So, any time we “change” a String, we are actually creating a new String in memory. Keep this in mind as we explore the methods of the String class.

You can see that when the primitive int variable age is modified on line 10, the memory location that contained its initial value (16) is simply overwritten (recycled) with the new value (17). For the String object message it works differently. Rather than overwriting the String “Hello” in memory, a brand new String object “Hello James” is created and the message reference variable then points to this new String in memory. Because the old String object “Hello” no longer has any references (arrows) pointing to it, the JVM will remove it from memory by an automatic process called garbage collection. So, any time we “change” a String, we are actually creating a new String in memory. Keep this in mind as we explore the methods of the String class.

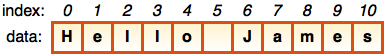

Fact #3: Strings are Indexed

The final important concept to understand about strings is that each character in a String has an index number. For example, you can think of the string “Hello James” being stored in memory like this:

The index of the first character always starts at 0. Indexes are important when we want to access specific characters or substrings within a string.

The index of the first character always starts at 0. Indexes are important when we want to access specific characters or substrings within a string.

Although each character in a string has an index, they are not easily indexable like other languages such as Python and C++. In other words, one cannot access a character directly using an index like so:

|

1 2 |

// WRONG way to access the first character of the message string System.out.print( message[0] ); // Syntax Error |

Instead, there are String methods such as charAt() and substring() to allow us to access parts of a string using indexes.

With these three facts understood, let’s look at some useful String methods.

Basic String Methods: length and charAt()

The length() method returns the total number of characters in a String object. Note that because strings are indexed from 0, this is not the same as the index of the last character in the string. For example, the length of the String “Hello James” is 11 but the index of the last character is actually 10.

The charAt() method returns the char (primitive type!) at a particular index.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

public class StringBasics { public static void main( String args[] ) { String s1 = "Hello There!"; // short-hand String s2 = new String( "Vik-20!" ); // longer way System.out.printf( "s1: \"%s\"\ns2: \"%s\"", s1, s2 ); // How many characters are in s1? System.out.printf( "\nLength of s1: %d\n", s1.length() ); // Use charAt() and a loop to reverse s2 System.out.print( "s2 reversed is: " ); for ( int count = s2.length() - 1; count >= 0; count-- ) System.out.printf( "%c", s2.charAt( count ) ); // s1 and s2 are unchanged! System.out.printf( "\ns1: \"%s\"\ns2: \"%s\"\n", s1, s2 ); } } |

s1: “Hello There!”

s2: “Vik-20!”

Length of s1: 12

s2 reversed is: !02-kiV

s1: “Hello There!”

s2: “Vik-20!”

Comparing Strings: equals(), equalsIgnoreCase(), and compareTo()

You know that we can’t use any of the relational operators (==, >, >=, <, <=, or !=) to compare string objects because these would compare the memory locations of the strings and not their actual contents. To get around this, we learned about the equals() method in 1-6.

The equals() method returns a true or false value depending on whether all of the characters in the current String object are exactly the same (including case) as the characters in a parameter String object. To check for equality, but ignore differences in upper or lower case, use the equalsIgnoreCase() method instead.

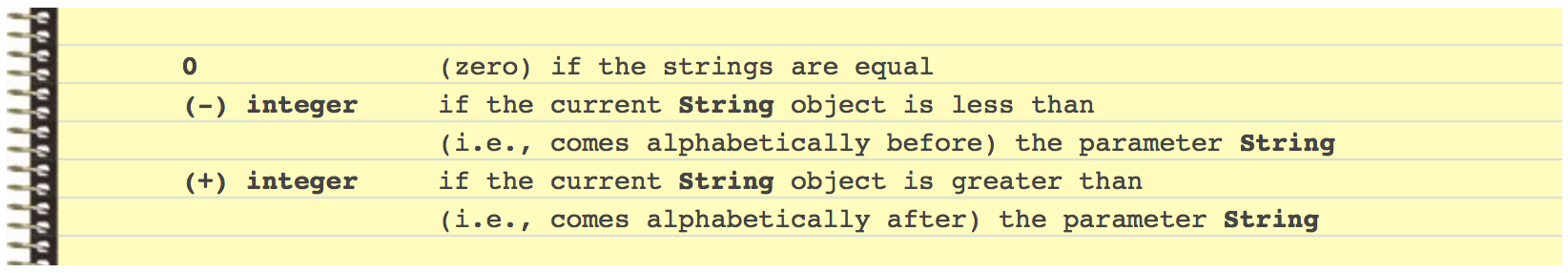

To compare two String objects to determine their alphabetical order you can use the compareTo() method. The compareTo() method returns one of three (integer) possibilities:

Here’s an example to demonstrate:

Here’s an example to demonstrate:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 |

public class StringCompare { public static void main( String args[] ) { String s1 = "Hello"; String s2 = "hello"; System.out.printf( "s1 = %s\ns2 = %s\n", s1, s2 ); // Check for equality if ( s1.equals( "hello" ) ) // false System.out.println( "s1 equals \"hello\"" ); else System.out.println( "s1 does not equal \"hello\"" ); // test for equality (ignore case) if ( s1.equalsIgnoreCase( s2 ) ) { // true System.out.printf( "%s equals %s with case ignored\n", s1, s2 ); } else { System.out.printf( "%s does not equal %s with case ignored\n", s1, s2 ); } // Compare alphabetical order s2 = "Jello"; System.out.printf( "s1.compareTo( s1 ) gives %d\n", s1.compareTo( s1 ) ); System.out.printf( "s1.compareTo( s2 ) gives %d\n", s1.compareTo( s2 ) ); System.out.printf( "s2.compareTo( s1 ) gives %d\n", s2.compareTo( s1 ) ); } } |

s1 = Hello

s2 = hello

s1 does not equal “hello”

Hello equals hello with case ignored

s1.compareTo( s1 ) gives 0

s1.compareTo( s2 ) gives -2

s2.compareTo( s1 ) gives 2

You’ll notice in the last two lines of output the compareTo() method gives -2 or +2. The 2 represents the difference in Unicode character value between the “H” in “Hello” (s1) and the “J” in “Jello” (s2).

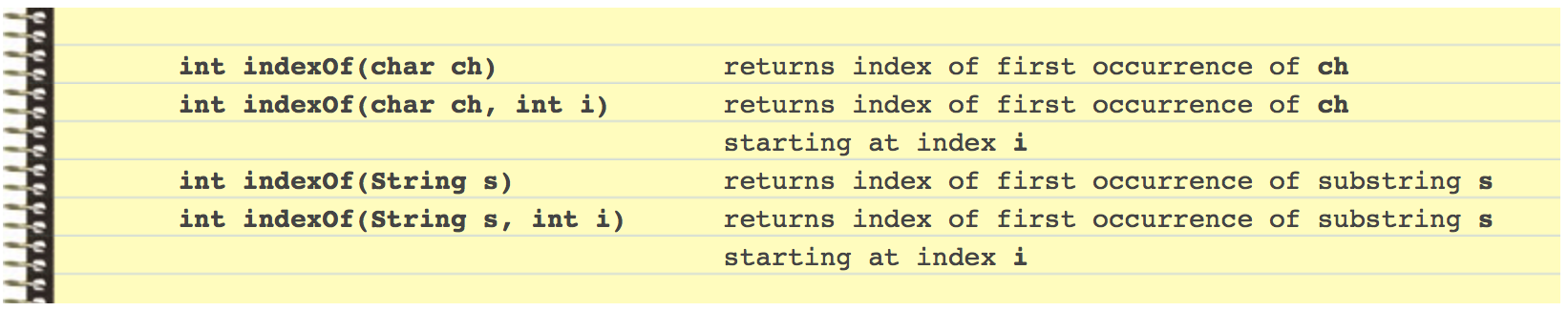

Indexing Strings: indexOf(), lastIndexOf(), and substring()

The indexOf() and lastIndexOf() methods allow us to find the index of a given char or substring within the current String object. If the char or substring cannot be found, -1 is returned. There are four overloaded versions of these methods:

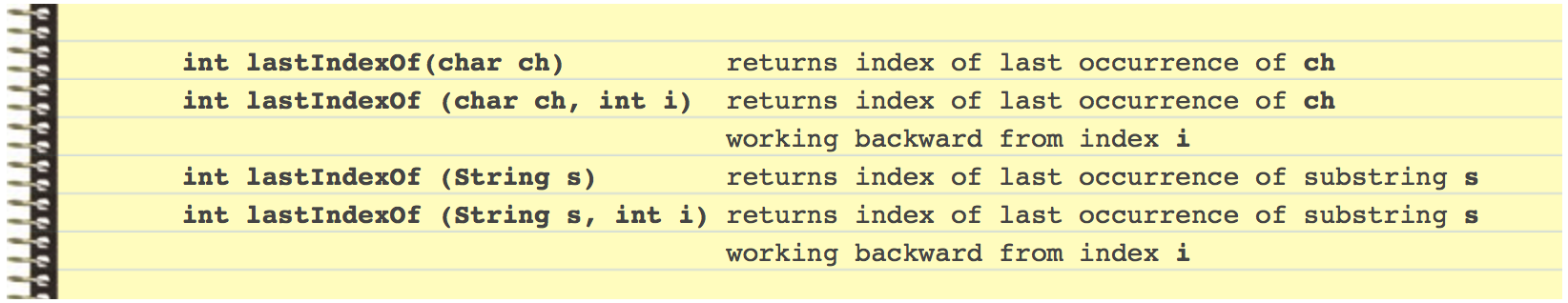

There are also four similar methods that search from the end of the string toward the front:

There are also four similar methods that search from the end of the string toward the front:

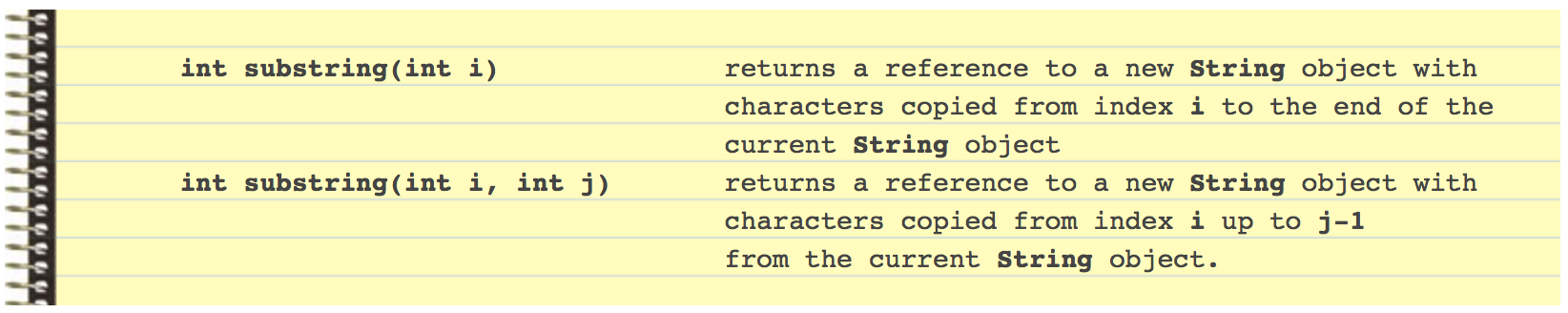

Finally, the substring() method returns a reference to a new String object made up of a span of characters copied from the current String object. There are two overloaded versions of this method:

Finally, the substring() method returns a reference to a new String object made up of a span of characters copied from the current String object. There are two overloaded versions of this method:

Here’s an example to demonstrate these methods:

Here’s an example to demonstrate these methods:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 |

public class StringIndexing { public static void main( String args[] ) { String letters = "123abc$ 123abc$"; // Display letters string with indices for reference System.out.println( "- - - - - 11111" ); System.out.println( "012345678901234" ); System.out.println( letters ); // Find FIRST occurence of a single char in a string System.out.printf( "'a' is at index %d\n", letters.indexOf( 'a' ) ); System.out.printf( "'x' is at index %d\n", letters.indexOf( 'x' ) ); System.out.printf( "'2' is at index %d\n", letters.indexOf( '2', 1 ) ); // Find LAST occurence of a single char in a string System.out.printf( "'a' is at index %d\n", letters.lastIndexOf( 'a' ) ); System.out.printf( "'x' is at index %d\n", letters.lastIndexOf( 'x' ) ); System.out.printf( "'2' is at index %d\n", letters.lastIndexOf( '2', 8 ) ); // Find FIRST occurence of a substring within a string System.out.printf( "\"abc\" starts at index %d\n", letters.indexOf( "abc" ) ); System.out.printf( "\"xyz\" starts at index %d\n", letters.indexOf( "xyz" ) ); System.out.printf( "\"abc\" starts at index %d\n", letters.indexOf( "abc", 4 ) ); // Find LAST occurence of a substring within a string System.out.printf( "\"abc\" starts at index %d\n", letters.lastIndexOf( "abc" ) ); System.out.printf( "\"xyz\" starts at index %d\n", letters.lastIndexOf( "xyz" ) ); System.out.printf( "\"abc\" starts at index %d\n", letters.lastIndexOf( "abc", 7 ) ); System.out.printf( "Substring from index 10 to end is \"%s\"\n", letters.substring( 10 ) ); System.out.printf( "Substring from index 3 up to, but not including 6 is \"%s\"\n", letters.substring( 3, 6 ) ); } } |

– – – – – 11111

012345678901234

123abc$ 123abc$

‘a’ is at index 3

‘x’ is at index -1

‘2’ is at index 1

‘a’ is at index 11

‘x’ is at index -1

‘2’ is at index 1

“abc” starts at index 3

“xyz” starts at index -1

“abc” starts at index 11

“abc” starts at index 11

“xyz” starts at index -1

“abc” starts at index 3

Substring from index 10 to end is “3abc$”

Substring from index 3 up to, but not including 6 is “abc”

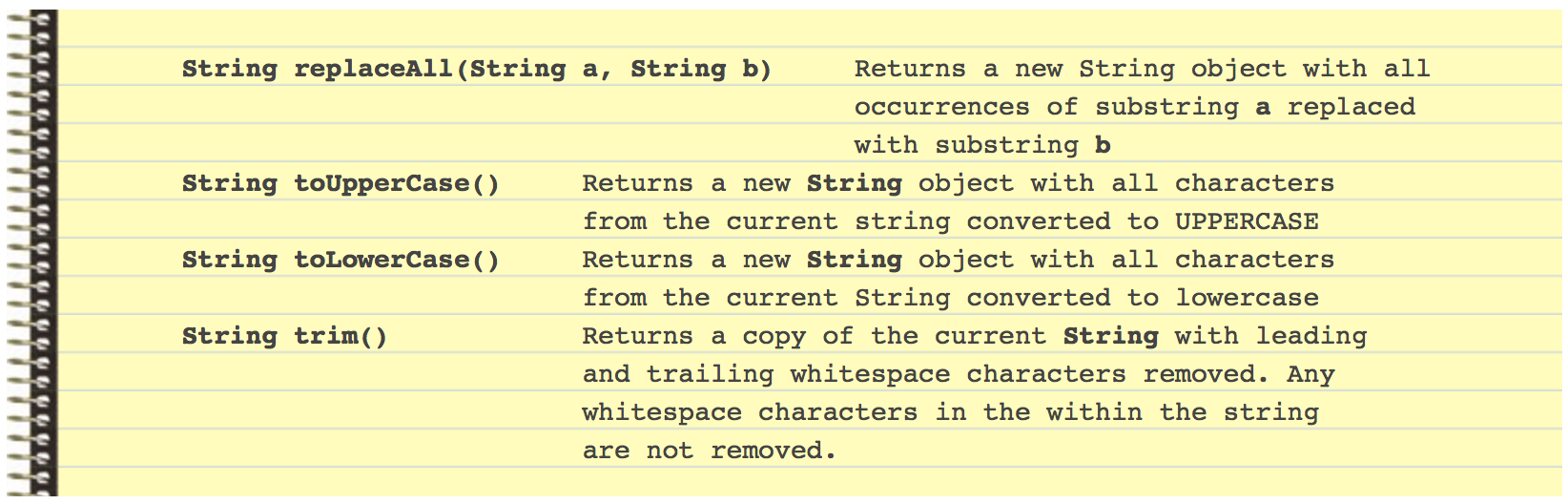

Modifying Strings: replaceAll(), toUpperCase(), toLowerCase(), trim()

Since String objects are immutable, one cannot actually modify a String. But there are some methods that will return a reference to a new copy of a String object with changes applied.

Here is a demonstration of these methods in action:

Here is a demonstration of these methods in action:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

public class StringModifying { public static void main( String args[] ) { String s1 = new String( "Hello, do YOU Love Java?" ); String s2 = new String( "\ttabs and spaces \n are \tgone \n " ); // All methods return a reference to a COPY of s1 or s2 with changes applied System.out.printf("Replace \"l\" with \"ha-\" in s1: %s\n\n", s1.replaceAll( "l", "ha" ) ); System.out.printf( "s1.toUpperCase() = %s\n", s1.toUpperCase() ); System.out.printf( "s1.toLowerCase() = %s\n\n", s1.toLowerCase() ); System.out.printf( "s2 before trim = \"%s\"\n\n", s2 ); System.out.printf( "s2 after trim = \"%s\"\n\n", s2.trim() ); // Original Strings are unchanged! System.out.printf( "s1 = %s\ns2 = \"%s\"\n\n", s1, s2 ); // How to actually "change" a string, use assignment (=) statement s1 = s1.toUpperCase(); s2 = s2.trim(); System.out.printf( "s1 = %s\ns2 = \"%s\"\n", s1, s2 ); } } |

Replace “l” with “ha-” in s1: Hehahao, do YOU Love Java?

s1.toUpperCase() = HELLO, DO YOU LOVE JAVA?

s1.toLowerCase() = hello, do you love java?

s2 before trim = ” tabs and spaces

are gone

”

s2 after trim = “tabs and spaces

are gone”

s1 = Hello, do YOU Love Java?

s2 = ” tabs and spaces

are gone

”

s1 = HELLO, DO YOU LOVE JAVA?

s2 = “tabs and spaces

are gone”

Again, none of these methods actually changes the original String object, they are simply returning a reference to a copy of a new String object with changes applied (which we are immediately printing). To actually change a String, you need to assign its reference variable to the new copy as shown on lines 17 and 18.

Creating a Formatted String: format()

The String class includes a special method called format() that takes the same parameters as printf() but instead of displaying a formatted string it returns a reference to a new String object with the desired formatting applied:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

import javax.swing.JOptionPane; public class StringFormat { public static void main( String args[] ) { String outputString = null; outputString = String.format( "%02d/%02d/%d $%5.2f", 12, 3, 2016, 12.345 ); JOptionPane.showMessageDialog( null, outputString ); } } |

Notice that I have not used the new keyword anywhere in this example to instantiate a String object. On line 5, the variable outputString is declared as a reference variable to a String object but this does not actually create a String object.

You can see the format() method in action on line 7. Unlike the other String class methods, the format() method is called using the String class name followed by .format(). The format() method itself instantiates a String object, applies the desired formatting to it, and returns a reference to the new String object which we assign to our outputString reference variable. At this point nothing has been displayed on the screen.

On line 8 we show the formatted outputString in a GUI dialog box. This is a particularly good example because the showMessageDialog() only accepts two parameters and does not support format specifiers directly. Without the ability to create a formatted String object this would not be possible.

NullPointerException Errors

Before we end, I want to mention a common exception that can occur when working with objects. Consider the following code:

|

1 2 |

String outputString = null; outputString = outputString.toUpperCase(); |

The first line is declaring a reference variable for a String object, but it does not actually point to a String object in memory yet. Because of this if we attempt to call the toUpperCase() method the program will crash with a NullPointerException. The point is that you need to be sure that a reference variable actually refers to an object in memory before attempting to call its methods.

You Try!

- Use the String.format() method to neatly round the final result of your GUI compound interest calculator (from 1-5) to 2 decimal places.

- The Character class has many useful methods for testing various char properties. These methods work like the methods of the Math class: they are part of the java.lang package so you don’t need to import the class, and you do not need it instantiate a Character object to use the methods, just use the class name Character. followed by the method you’d like to call. Write a program to demonstrate the following methods: isDigit(), isLetter(), isLetterOrDigit(), isLowerCase(), isUpperCase(), toUpperCase(), and toLowerCase().

- Let’s make our own methods that operate on strings. Complete all of the methods below including the main() method to demonstrate their use.

12345678910111213141516171819202122232425262728293031323334353637383940414243444546474849505152535455public class FunWithStrings {public static void main(String[] args) {.. ADD CODE HERE TO DEMO ALL METHODS BELOW ..}// Takes a String parameter and returns true if the string contains only// letters (a-z or A-Z), or false if it contains any non-letters// (e.g., digits 0-9 or punctuation like $, !.)public static boolean isOnlyLetters( String str ) {.. ADD YOUR CODE HERE ..}// Takes a char and String parameter and counts and returns the number// of times the character occurs in the given string (0 if no matches).public static int countChars( char ch, String str ) {.. ADD YOUR CODE HERE ..}// Takes a String parameter and returns a reference to a new String object// that contains the same characters as the parameter String except in// reverse order. The original parameter String should not be changed.public static String reverseString( String str ) {.. ADD YOUR CODE HERE ..}// A palindrome is a word or phrase that is spelled the same way forward and// backward. For example, "mom", "racecar", "able was I ere I saw elba".//// This method takes a String parameter and returns true if the String// is pallindromic or false otherwise. Hint: Can you reuse one of your// other methods to simplify this?public static boolean isPalindrome( String str) {.. ADD YOUR CODE HERE ..}// Returns a string containing the first HTML tag found in text (including// the < and > brackets) or null if no valid tag is found. A tag is any// substring starting with < and ending with the closest >.public static String findFirstHTMLTag(String text) {.. ADD YOUR CODE HERE ..}} - Create a Cities application that prompts the user for a series of city names and then displays the number of city names entered and then the name of the city (in UPPERCASE) with the most characters of those entered. The application output should look similar to the following:

Enter a city name (or ‘done’ to stop): Toronto

Enter a city name (or ‘done’ to stop): Vancouver

Enter a city name (or ‘done’ to stop): Montreal

Enter a city name (or ‘done’ to stop): done

3 names were entered, the longest was VANCOUVER!